Peter Weir's

The Truman Show

The Truman Show

Reality TV.

an analysis for 2025

PhD Candidate | Macquarie University

Abstract

This paper offers a Deleuzian reading of The Truman Show (dir. Peter Weir, 1998), examining how the film deploys key taxonomic elements from Gilles Deleuze’s Cinema 1: The Movement-Image and Cinema 2: The Time-Image. It argues that Weir’s formal choices (his framing, camera placement, shot durations, and the construction of Truman’s world) uses Deleuze’s image-types to reflect and critique the logics of surveillance, spectacle, and subjectivity.

This analysis identifies moments in the film where perception-images dominate, revealing the extent to which Truman is seen and sees himself within a controlled schema of movement and reaction. It further explores the emergence of time-images, especially as Truman begins to question the consistency of his world, introducing irrational cuts, false continuity, and crises of belief. By mapping Deleuze’s taxonomies onto the narrative and aesthetic structure of the film, this paper contends that The Truman Show not only exemplifies the transition from classical to modern cinema but also allegorises the shift in spectatorship and agency in the late 20th century. Ultimately, the film operates as a meta-cinematic reflection on the conditions of image-production and human freedom within the regimes of mediated life

.svg)

Overview of The Truman Show

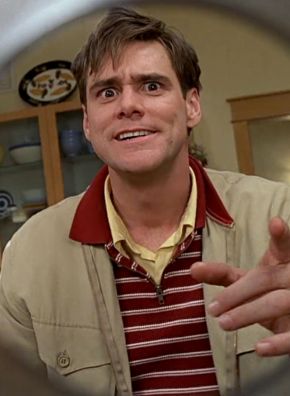

Released in 1998 and directed by Australian filmmaker Peter Weir, The Truman Show is a genre-blending cinematic work that occupies the space between satire, science fiction, and psychological drama. The film was written by Andrew Niccol and stars Jim Carrey in a dramatic role as Truman Burbank, a seemingly ordinary man who slowly comes to realise that his entire life has been the subject of a meticulously orchestrated television programme. Broadcast live 24/7 to a global audience, Truman’s world is entirely artificial. His everyday world is constructed within a massive geodesic dome that is populated by actors and extras playing roles in an elaborately scripted narrative.

Truman Burbank and Seahaven

The character of Truman is sincere, good-natured, and naive, but he is directed entirely by the cues and codes of the world around him. Unaware of the deception, he lives in the idyllic town of Seahaven, a simulacrum of 1950s American suburbia. This picturesque ‘haven’ is entirely clean, safe, and endlessly repetitive. There is no graffiti on the walls of Seahaven. The environment is engineered to eliminate risk and ensure compliance, (Truman himself works in a job selling insurance!). The world subtly disciplines Truman’s desires through advertising, fake news, and fear-mongering (notably around travel and the ocean).

Through a Deleuzian lens, Seahaven is not just a set, it is a closed system of perception and action, governed by what Deleuze called a sensory-motor schema. At the heart of this constructed reality is Christof (played by Ed Harris), the film’s godlike creator-director who watches Truman from the “moon”. This is a control room embedded in the dome’s structure, posing as the moon. Christof’s role is central to the philosophical tensions within the film. As the sole (it appears) architect of the system, he symbolises the visible hand behind the spectacle, offering the audience a defined antagonist, in contrast to a faceless swirl of chaotic influence and manipulation of a contemporary (i.e. 2025) “Auto-control structure” that can be auto-phenomenological. Christof is a face to the ubiquitous surveillance. Yet his visibility is precisely what distinguishes The Truman Show from more insidious forms of real-world control: we rarely encounter the architect in our lived realities. Christof’s presence satisfies a narrative need for an antagonist, but in doing so, it also reveals our dependence on visualising power in order to resist it.

A warning about our loss of agency

This film critiques, and indicates, that this very visibility offers a false sense of agency; and without an identifiable oppressor, resistance becomes amorphous, uncertain, and internalised. (It is largely through poor maintenance and human errors that the veil of Seahaven is pulled back enough for Truman’s suspicions to be ratified).

This inability to resist is a point that resonates strongly with Deleuze’s critique of disciplinary and control societies, when he speaks of “ultra-rapid forms of free-floating control that replaced the old disciplines operating in the time frame of a closed system” (Deleuze 1992) Socially,

The Truman Show arrived at the end of the 20th century, at the emergence of reality television and just before the digital explosion of surveillance, global data systems, and social media. It reflects (the then, potential,) contemporary anxieties about authenticity, media saturation, and the commodification of the self. The film examines the ethics of spectatorship, the power of media corporations, and a thin line between entertainment and manipulation that in 2025 are accepted as one.

Deleuze at an Overall level

While The Truman Show functions on one level as a mainstream psychological drama and media satire, its deeper philosophical intent emerges when read through the lens of Gilles Deleuze’s Cinema 1: The Movement-Image and Cinema 2: The Time-Image. Deleuze’s taxonomy offers a framework for analysing how films organise perception, action, and temporality and how these cinematic arrangements reflect (or resist) dominant structures of thought and control.

After the first Act, we retrospectively see Truman’s early life in Seahaven. The depiction is an example of the movement-image in action. His world is a closed, coherent system in which perception-images (what Truman sees) are tightly coupled to action-images (how he responds). He is on auto-pilot. The sensory-motor schema is intact, and Truman’s responses are conditioned and predictable. In this way the world he occupies functions like classical cinema. There are clear stable spatiotemporal coordinates and logical causality. Everything he perceives is mediated through the smooth operation of Christof’s constructed world. If we put ourselves in the shoes of the audience (in the world of Weir’s film) there is perhaps not much narrative tension, just the voyeuristic payoff of watching Truman.

However, as the cracks begin to appear, through minor disruptions like a falling stage light (named Sirius – i.e. stars falling from the sky), a radio frequency glitch, or a familiar face out of place, Truman enters a crisis of the sensory-motor schema. His perception is no longer coordinated with predictable action; instead, there is now a gap that emerges between stimulus and response. These gaps, demarked what Deleuze calls opsigns, sono-signs and crysigns, indicate the shift to that of the time-image. This is a cinematic logic in which the linearity of action breaks down. According to Deleuze this is where time becomes visible as an image, and we, the audience can experience it. From this point forward Truman no longer merely acts; he reflects, hesitates, suspects, and these interruptions gain amplitude and intensity. The film increasingly adopts cinematographic tactics that are aligned with modern cinema. The montages become longer, the control room is revealed, the is subjective framing (e.g. hidden cameras), and moments of existential stillness. These shifts parallel Truman’s inner transformation from benign, unknowing subject eventually to being resistor.

The entire film can be thought of as moving from Movement-image to Time-image, and Truman eventually ascending (literally) into another dimension through his emancipation from SeaHaven. There is another kind of image that is presented to us on this journey, that of the Neuro-image.

To look at how Weir achieves this let’s view scenes from the film through the elements of Deleuze’s taxonomy of cinema. The selected scenes are those that are key moments where Weir’s themes emerge. Whilst there are many interpretations by Deleuzian cinema scholars over how many images and signs there are,(numerous and ever-increasing) I am considering the Cinema1 and Cinema2 taxonomy as “generative device(s) meant to create new terms for talking about new ways of seeing” (Bogue 2003). Hence, the taxonomic elements[1] I will use are:

- Frame, Shot, Montage

- Movement-image, (Perception, affectation, action)

- Time-image (Perception, affectation, action)

- Opsign, Sonosign, Sonosign

- Crystal image

- Any-space-whatever

Certainly. Gilles Deleuze’s concepts of frame, shot, and montage are foundational to his Cinema 1: The Movement-Image and Cinema 2: The Time-Image. Though he borrows these terms from classical film theory, he reinterprets them through his own philosophical lens, especially drawing on Bergson’s philosophy of movement and time.

Gilles Deleuze Taxonomy of Cinema

Frame, Shot, Montage

Frame, Shot and Montage : Camera Viewpoints

Weir uses three categories of camera viewpoints; 1) spy cameras in Seahaven, 2) cameras presenting the behind-the-scenes view of The Truman Show, and 3) cameras that are in the world of the film but outside the diegetic world.

Seahaven Spycam Category

Once the opening creadits are complete, we are immersed in the these diegetic cameras. They are within the narrative world and they have recognisable surveillance qualities. They are fisheye lenses, object-embedded points-of-views (e.g., bathroom mirror, Truman’s car dashboard, vending machine). These frames have explicit placement and we know someone (Christof, the controlroom employees and the in-world audience (the security guards, the waitresses, the man-in-the-tub) is watching.

Figure 22: Spycam surveillance of Truman

The shots from these camera actively construct a subject under surveillance. The in-world audience viewer’s position overlaps with the gaze of power that is Christof, acting as Seahaven’s pseudo-god. We, the audience succumb to this point of view because Weir holds us in this context for the first 14 mins of the film until he switches to the BTS.

Behind-the-scenes / Mockumentary

The shots from these camera actively construct a subject under surveillance. The in-world audience viewer’s position overlaps with the gaze of power that is Christof, acting as Seahaven’s pseudo-god. We, the audience succumb to this point of view because Weir holds us in this context for the first 14 mins of the film until he switches to the BTS.

Figure 23: The (BTS) Weekly review of The Truman Show

Outer World

Weir gives us another perspective. This is delivered by the third category of cameras. These show us the control room, Lauren’s home, a bar with fans watching Truman and other viewers of Truman’s life in Seahaven. These shots reinforce a layered reality as we see the watchers of Truman, and thus watch the watchers.

Figure 24: The control room in the moon, replete with control-room cat

This builds a montage of shots (for us in the context of sitting in a theatre) that are no longer causally linked, but juxtaposed, reflecting different regimes of time and perception. These scenes displace our position of stability. We are forced to reflect, “Who are we now? The viewer, the god, the rebel, or Truman?”

The Fourth category, Cinematic (non-spycam) Shots Within Seahaven

Figure 25 : Slow pan dolly movement shot at Truman's office

These shots disrupt the system. They break the illusion that the entire Seahaven world is mediated only by surveillance. They introduce ambiguity in the frame and force the question, “Who is the observer now?” If Weir is pulling us in to the perspective of the The Truman Show viewers, then this creates a crack in that image system. This is the mechanism Deleuze attributes to the emergence of time-image cinema. These cinematic shots generate a discombobulated perspective.

We, the auditorium audience, are no longer anchored to a consistent point of view (Christof, Truman, or the outside world of the control room etc). These purely cinematic shots in Seahaven suspend our ability to locate ourselves logically in the diegesis.

They fracture the sensory-motor schema and suggest that it is no longer the case that actions are leading clearly to reactions, or perceptions to outcomes. They initiate a crisis of the image: Truman’s world isn’t just fake, which we already know from the outset, but it is now incoherent, from the inside. Deleuze calls this a shift from “the movement-image (perception → action)” to “the time-image (perception → hesitation, reflection, falsity).”

Intent may be a factor in this. Weir may have decided to integrate cinematic shots in to the Seahaven montages for practical reasons such as needing to not suffocate the auditorium audience with constant fish eye, spycam shots for the majority of the film having successfully established the concept of the world of surveillance.

However, the cinematic images tend to be at high impact emotional moments, most notably at the conclusion of the film when Truman’s sailing boat approaches the wall of the dome.

The Truman Show as Cinema of the Brain

Deleuze (especially via Patricia Pisters’ elaboration) talks about the brain as screen. This is direct impact on our brains. In post-classical cinema, thought happens within the image itself, not as something the auditorium audience would reflect upon after watching.

These non-diegetic shots in Seahaven are not explainable within the logic of the diegesis. (The cameras can’t possibly be there physically, and even if they were, the control room editors and directors could not react in real-time to edit and fully create the emotional drama of the unfolding action). Instead, these shots create internal dissonance and the auditorium audience is invited to inhabit multiple levels of consciousness at once. These are; empathy with Truman’s innocence, repugnance at Christof’s control, agog at the world’s spectatorship, and finally, shame in their own complicity.

In this way, the Truman Show moves towards the virtual and we view the “narrative (storytelling creating an indeterminate filmic event) as a noosign”. (Deamer 2016).

Relevance and Limits of The Truman Show Today

The Truman Show once served as a speculative mirror on surveillance, control, and authenticity. In 2025, it feels less like speculative fiction and more like documentary!

Through Deleuze, I wanted to explore whether The Truman Show would still provoke insight or just serve as a nostalgic artefact, given how society has acclimated to surveillance and control structures. The film placed the 1997 auditorium audience in an in-between space indicating that collectively with needed to be wary of the tendencies of spectacle leading to the loss of privacy, and control over our own thoughts.

A 2025 audience watches not knowing that the film’s earlier warnings were acknowledged in the 1990s but not acted upon. As a result, society chose accommodation over resistance.

Deleuze, Defamiliarisation, and the Movement-to-Time Image Shift

Deleuze’s taxonomy has demonstrated usefulness in defamiliarising the all-too-familiar. Applied to The Truman Show it shows the invisible forces shaping perception and action that are all around us in 2025.

The analysis also unveils the results of the efforts (and perhaps explicit intent) of the director and writer at attempting to thread the needle of propaganda. Weir is trying to warn us, his 'art' has a message. He is seeking to control our behaviour, through cinema.

The Neuro-Image and its Possible (In)Applicability

Patricia Pisters’ neuro-image theory is introduced as a potentially richer lens for today’s fractured, multi-screen realities, though its complexity and abstraction are acknowledged. The Truman Show doesn’t fully fit the neuro-image model because it remains largely self-contained, although Weir’s abandoned plan to film live audiences watching the film would have moved it in that direction. Neuro-image is positioned as a cinema of the brain, following Deleuze’s distinction from the cinema of the body

Surveillance, Acquiescence, and Cultural Complacency

A major analytical thread here explores the viewer positioning in The Truman Show: are we audience, god, technician, or part of the in-world society? The constant shifting between diegetic and extra-diegetic frames disorients and prevents easy identification. This echoes a postmodern disembodiment.

We may think that this culminates in a question. With all of the surveillance, what can we do with this information and knowledge? Are we not the creators, the surveyed, the surveyers, etc. Is it not only the massive computer power of video and audio collection, overlayed with the analytical abilities for Artificial intelligence that can make sense of the fragments images of us? Could there possibly be any locus of control and intent. If all worlds are fictional and we are decentered, can we act? Is our collective voice no longer able to push back on the actors of control?

Conclusion

The Truman Show once served as a speculative mirror on surveillance, control, and authenticity. In 2025, it feels less like speculative fiction and more like documentary.

If all worlds are fictional and we are decentered, can we act? Is our collective voice no longer able to push back on the actors of control?

CODA

Weir's Cameras

Before examining the scenes, and to give context to the analysis of them, it is necessary to deal with one of the dominant aspects of film that strongly aligns with (or represents) Deleuze’s Frame, Shot and Montage.

New Terms

Some New Terms that arose from the analysis

- Emerging islands – recurring cinematic motifs that help construct the protagonist’s awareness.

- Lightning strikes – disruptive moments that fracture the movement-image and reveal another layer of reality.

- Flash mobs/flesh mobs – spontaneous synchronisations in the extras’ behaviour, symbolic of programmed collective compliance.

- Viewer disorientation as ethical paralysis – knowing too much but being positioned nowhere to act from.

The Secrets of Nefertiti's Bust

The Secrets of Nefertiti's Bust